马德琳·奥尔布赖特,美国历史上第一位女性国务卿。如今81岁的她,1937年5月出生在前捷克斯洛伐克一个外交官家庭。两岁时,为了躲避纳粹统治,一家逃往伦敦;十一岁时跟随父母移居美国。喜欢着红裙的她,从容面对90年代国际舞台的惊涛骇浪,被称为红裙“铁娘子”。本期我对话奥尔布赖特女士,讨论她和我眼中的世界。

搞不好,多年后你我开始想念冷战。

1991年末苏联解体后,那种显著的、集团性的、各自以资本主义与共产主义意识形态为旗帜的制度性对抗已不复存在,冷战结束。自1974年葡萄牙康乃馨革命到1991年苏联解体,60多个国家在第三次民主化浪潮中倒戈民主,虽然不少仍属于半权威(semi-authoritarian)政体,世界却早已沸腾一片。《历史的终结》、《文明的冲突》纷纷上架。似乎民主体制将开自动档迅速驶向终点;冲突的单位将由民族国家(nation state)被不同的文明共同体(civilizations)取代。于是世界进入美国主导的单极时刻(unipolar moment),经济、军事、政治与意识形态全面称霸。

然而特朗普的胜选和欧洲极右势力的泛起,给民主世界泼了一盆冷水。历史似乎回归了,还喘着复仇的粗气;文明间的冲突并未凸显,战争依旧以国家为主导单位(参见:恐袭后的悖论)。世界回到了新森林法则下的多级格局——美国、中国、俄罗斯。向往和平的你我,也许更需要一点谨慎不乐观。历史地看,相对于两极世界,单极世界(uni-polarity)冲突最少,虽然美国冷战后大小有七次战争;而两极格局(bi-polarity)往往比多极格局(multi-polarity)更稳定,美苏争霸的代理人战争相比1945年以前算是小巫见大巫;多级世界又以不平衡的多级格局(unbalanced multipolarity)最为危险,尤其当具有优势力量的大国(preponderant power),既感到强大,又感到不安(a curious sense of feeling both strong and vulnerable)。例子比如一战前的德意志帝国,二战前欧洲的纳粹德国、东亚的日本帝国。

在自由主义盛行的单极时刻,民主理论得到了空前发展,主要有三。第一是民主和平理论(democratic peace theory)。不是说民主国家不会发动战争,而是说民主国家与民主国家之间鲜有交战。不但如此,民主国家战斗力往往比非民主国家强,于是民主政体很关键,最好世界就是一大块和平共处的民主共同体。第二是经济相互依赖理论(economic interdependence theory)。该理论假设任何理性的领导人不会轻易发动战争,因而损害现有体系下的经济利益。于是乎,一个开放的,贸易与投资流动顺畅的经济共同体,将会带来长远的和平。不少人将中美和平寄托于这一点。第三是自由制度主义理论(liberal institutionalism)。只要将国家嵌入一个自由民主的国际体系下,任何纷争都可以依靠国际组织的法律框架调解。换句话说,只要中国加入WTO,就能在国际贸易体系里遵守规则,贸易纷争都能得到公平有效的裁决。然而,我们看到,似乎这些具有前瞻性的理论远见,并不完全与当前国际现实对接。不是说民主理论有错,而是任何理论都有其适用的条件。民主理论,尤其是理论2、3,在单极世界中,尤其是以美国为主导的自由主义秩序(又称霸权)下,才比较适用。当世界趋于多极,即便我们再渴望理论2、3成立,现实的轨迹往往与理想偏离。

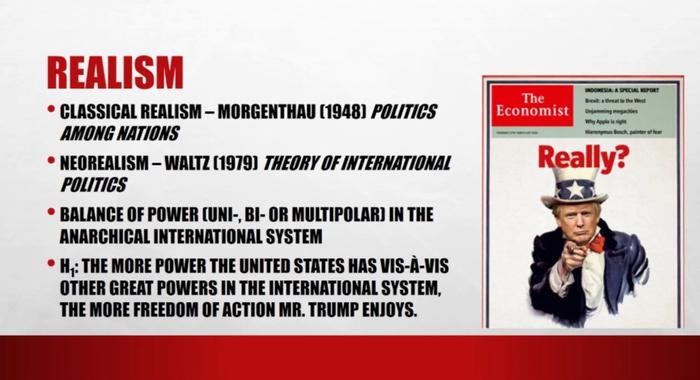

当然,不少人认为核武器的存在消除了大国间传统战争(conventional war)的可能,所谓的核和平理论(nuclear peace theory)。面对可以毁灭世界多次的热核战争,不敢说国与国平等,但至少领导人在核威慑面前都得认怂。然而,即便我们对核未来充满信心,也难以忽视这样一个独立存在的现实:当世界格局逐渐走向一超多强的多级格局,尤其是在修昔底德陷阱的历史阴影下,以力量平衡(balance of power)为代表的现实主义(realism)将回归我们的视野。

平衡外交本身不是坏事,但需要的技巧和运气,远高于在单极或两极格局中所需。这也意味着,不仅仅需要更加智慧的领导人(一个俾斯麦和基辛格还不够,要一连串的俾斯麦和基辛格),民众的理性和历史观都需要拔高一个层次。不仅仅要对现实的轮廓要有清晰的认识,还要有基于原则的憧憬,在合理的历史观下,将理想照进现实。毕竟,人类的历史既不是线性进步(linear progressive),又不是环形更迭(cyclical),更不是逆流而下(regressive)。当历史的主角,从少数人变为更多数时,也意味着承担历史风险的我们,更有必要理解历史。我曾经列过一个单子,里面包括:不要被叫嚣“终有一战”的阴谋论者蛊惑,不要轻易转发放大冲突的标题党文章,不要把政客的表演归咎于整个民族国家,不要放弃独立思考和多方核实信息的责任。一方面,不要被单一的意识形态过度左右;另一方面做到有所坚持,不迷惘于短线的历史波动。既不教条,又不犬儒,这样冷战不致于成为最优解,甚至成为比现实更美好的版本。对于这一点,我们可以谨慎乐观。

本期羊说,我对话了美国历史上首位女性国务卿马德琳·奥尔布赖特。主题分别为政治正确、法西斯和难民潮。奥尔布赖特于1997年至2001年任美国第64任国务卿,如今81岁的她,1937年5月出生在前捷克斯洛伐克一个外交官家庭。两岁时,为了躲避纳粹统治,一家逃往伦敦;十一岁时跟随父母移居美国。一家原本是犹太人,为了忘却二战中犹太人的悲惨经历,一家人在美国改信天主教。奥尔布赖特是后来在报道中才得知自己曾经是犹太人。

童年经历使奥尔布赖特对难民颇为同情,她小时候何曾不是一个难民呢?当年满头金发、有一双大眼睛、可爱的小胖姑娘,后来拿到了哥大政治学博士学位。她当过国际关系学院院长,教过的学生中有后来的第二位女国务卿赖斯。除了英语和捷克语,奥尔布赖特通晓波兰语、俄语和法语,担任过克林顿时期美国驻联合国大使,59岁时担任女国务卿。喜欢着红裙的她,从容面对90年代国际舞台的惊涛骇浪,被称为红裙“铁娘子”。她曾敦促克林顿总统用“战斧”惩罚被称为“巴尔干屠夫”的米洛舍维奇。美国《新闻周刊》以《冬日母狮》为题,称她为“战争女人”。她常把“美国是一个不可或缺的国家”挂在口上,被华盛顿政界称为“一条路走到黑的决策者”。奥尔布赖特有一个有趣的癖好,就是通过别挂的装饰胸针(brooch)来传递外交信号。她2010年出版的《读我的胸针》也是她在中国出版的第一本书。如今在史密森博物馆展览了奥尔布赖特两百多个不同的胸针。

对话文字

Madeleine Albright

Duration: 7:15

Interviewed: 4/19/2018

On Political Correctness

谈政治正确

YANG: Hi, my name is Yang. In his Democratic Vistas published in 1871, Walt Whitman said that the cause of democracy is sometimes aided not by the best man only, but sometimes more by those that provoke it, by the combats they arouse. He did not mind a little healthy rudeness, what many people today would call the “politically incorrect." However, what he foresaw as an exhilarating adventure has been replaced by the up-and-down of the delicate "democratic experiment," with words in recent decades associated with liberal democracy shifting from the triumphant to the fatalistic: overstretched, set-back, fragility, rise and fall. So my question is, what do you think of the health of free speech on campus as a barometer of the health of democracy at large, and in the spirit of Whitman, how to strike a balance between paying due respect to the concrete contours of reality and giving enough space to that healthy, productive, rudeness?

向杨:你好,我叫向杨。在他1971年发表的《展望民主》一书中,沃尔特·惠特曼说道,有时民主事业不仅借力于那帮最优秀的人,有时更多地是靠一帮捣蛋的人,他们引起的争议反而有助于民主。惠特曼不介意民主进程中出现的“健康向上的粗鲁”,也就是如今很多人说的“政治不正确”。但是,他当时所预见的那种“惊心大冒险”如今却演变成了一场波折不断、如履薄冰的“民主实验”。与自由民主相关的词汇也在近几十年里,由胜利者的狂欢转为宿命论的惆怅:过度扩张、挫折不断、脆弱性、盛衰更迭云云。所以我的问题是,把校园里的言论自由程度作为民主整体健康程度的指标,你怎么看?如果顺着惠特曼的精神,应该怎样把握一个平衡,一方面给事实的清晰轮廓以尊重,另一方面又能给那种 “健康向上的粗鲁”以足够的生存空间?

(注:沃尔特·惠特曼,美国诗人、散文家、新闻工作者及人文主义者。他身处于超验主义与现实主义间的变革时期,著作兼并了二者的文风。惠特曼是美国文坛中最伟大的诗人之一,有自由诗之父的美誉)

MADELEINE ALBRIGHT: Well, one of the things that I also—is on my to-do list—is that we have to learn to have civil discussions with people that we disagree with. And I think that that is a part that is, one, essential for democracy but certainly essential at a university setting, and therefore I do believe in the importance of listening to people that I disagree with. And I, by the way, when I teach, I say to people, "You all know I'm a card-carrying Democrat. And I want you to disagree with me." And I do think that part of what has to happen is to encourage civil disagreement and try to figure out what the other person is saying and why, and therefore I do believe that more than other places, that on campuses there needs to be that sense that we welcome discussions that are carried on in a civil way. I'm opposed to violence, but I do think that what we really need to do is have the possibility to have that discussion, and that it strengthens democracy in that particular way. And I do think that it helps us all to be pushed and to have our thinking disrupted. I think that is a very important part [2:30] of democracy.

玛德琳·奥尔布赖特:嗯,有一点——在我的计划列表之中——就是我们要学会与持有异见的人进行文明对话。对民主而言,我认为这是非常必要的一点。在大学的环境里更是如此。因此,我坚信倾听与我意见不一致的观点至关重要。此外,我在教学时,会告诉学生:“你们也知道,我是一名坚定的民主党员,但我希望大家反驳我的观点。”我也坚信,社会需要的是鼓励公民持有异见,并且试着弄清这些异见是什么以及背后的成因。也因此,我认为,比起其他任何地方,在大学里更需要有这种氛围,就是鼓励大家进行文明的对话。我反对使用暴力,但我认为我们真的需要推动各方展开对话,那样自然会巩固民主。我深信,我们的思考时常遭受排斥和扰乱,对我们其实都有好处。我认为这是民主社会中非常重要的一部分。

YANG: Thank you.

向杨:谢谢。

On Fascism

谈法西斯

MADELEINE ALBRIGHT: My family were victims of fascism, and I have often tried to figure out what it is, what led to the killing of millions of people because they were Jewish and various other kinds of Slavs, and why would that have even happened. And so I followed very much the kinds of things that have been going on, and then basically, also the kind of changes that have been taking place in Europe, of our allies, of the Turks and the Hungarians and the Poles. And then what had been happening in the Philippines and Venezuela just generally.

玛德琳·奥尔布赖特:我的家人受法西斯迫害,所以我一直都在努力搞清,是什么原因导致几百万人遭到屠杀,就单单因为他们的犹太人身份或是斯拉夫人的出身吗?为什么这样的事会发生。因此,我关注了很多当下仍存的此类事情,当然也包括正在发生变化的地方,像在欧洲啊、美国的盟国啊、土耳其、匈牙利以及波兰。还有总体上在菲律宾和委内瑞拉发生的一些变化。

And I think that the thing that I was looking for was, what is our day's fascism? And the bottom line is, fascism is hard to define. And just finding a definition, but basically, just briefly, I think it is when a leader identifies with one particular national or tribal group to the exclusion of others, and feels that the others are people that don't deserve any individual rights, very much kind of an us-versus-them. And then is able to really use democratic institutions to undermine democracy, because he does not believe in democracy in some form or another, and therefore, seeing the press as the enemy of the people, and thinking that the judicial branches are useless, and just generally, not understanding democratic institutions. And then, using new forms of information, propaganda, to motivate people to think that there are simple answers to very complicated problems, and ultimately—and I think this is the part that is very hard to kind of really pinpoint—is the use of any tool whatsoever to gain and keep power including violence. So a bully with an army. But I think those are the kind of general aspects, and they are really demonstrated in different ways—were initially, and are now. And the book is really historical, because I wanted to understand it, so it does begin with Mussolini and Hitler, and then kind of traces some of those points that I've made.

我想,我在寻找的一点就是,我们这个时代的法西斯是什么?关键的一点是,法西斯本身很难定义。我找到的一个定义是,本质上,简单来说,我认为如果一个领导人将一个特定的国家或部落群体视为与众不同,且认为群体外的其他人并不享有任何个体权利,相当于把人分为“我们”与“他们”。然后就开始利用民主体制来蚕食民主,因为他并不信任任何一种形式的民主,故而会将媒体视作是人民的敌人,认为司法机构毫无用处,总的老说,他自己也不理解民主体制。然后呢,借着新形的咨讯、宣传手段来鼓动人们,让人们觉得复杂问题有所谓的简单答案。最终——我认为这一步基本上很难准确定位——就是利用任何手段来巩固权力,包括使用暴力的权力。就是一个恶霸拥有了军队。不过这些都是概括而言,实际上它们的体现形式各有不同,一开始是这样,现在也是如此。我那本关于法西斯的书其实是本历史书,因为我想理解法西斯的成因。因此,书以墨索里尼和希特勒开始,然后逐渐铺开来讲刚才我提到的几点。

On Refugees

谈难民

I really do think this country and other countries were built on diversity and having a sense that refugees and immigrants are people that want to contribute to their country. And by the way, I believe that most people would prefer to live in the country where they were born, because they have the language and the family. And so to assume that they're just coming here in order to do drugs or rape people or be terrorists, I think, is ridiculous. And so I think what we need to keep explaining is that our country is built on diversity, and then help the people to become part of the system here. By the way, not only did I—Henry Kissinger said to me in that phone call, "You know, Madeleine, you have taken away my one unique characteristic of being an immigrant Secretary of State." And I said, "No, Henry, I don't have an accent." [LAUGHTER] But I do think that, without being self-serving, immigrants have done a lot for this country, and we need to keep persuading people that they want to be part of it. And it goes to a very basic issue—what is going on now? Our policies are based on fear. And to be an American, our policies have to be based on hope. And bringing people here will in fact provide hope. And David Miliband, who's head of the International Rescue Committee, said the following thing: "More people—Syrians—died in this chemical attack than have been brought into the United States. Forty-four Syrians have been brought into the United States this year.” Pretty outrageous.

我认为美国和其他很多国家都是建立在多样性之上的,并且应该有着一个共识,即难民和移民希望能为所到的国家做出贡献。当然,我相信大部分人都希望能在自己出生的国家生活,因为在那里他们说母语、有家人。所以,要说他们来美国是为了贩毒或是强奸别人或是当恐怖分子,其实很荒谬。所以我们要不停地解释,美国是一个包容多样的国家,并帮助移民融入社会。不仅仅是我这么认为——亨利·基辛格有一次打电话给我说:“玛德琳,你让我作为移民国务卿的特色黯然淡去了啊。”然后我说:“不·亨利,我可没有你那种外国口音。”[笑] (注:基辛格是出生于德国的犹太人,15岁逃离纳粹迫害最后来到美国。奥尔布赖特是出生于捷克斯洛伐克的犹太人,1938年慕尼黑协定之后,家人逃离捷克。两个人都是美国历史上有移民背景的国务卿)所以我觉得,与其说自私自利,不如说移民为美国做了很多贡献。我们要不断地向人们解释,移民想要融入我们的社会。这就涉及一个非常基本的问题——当下发生了什么?我们当下的政策是基于恐惧。身为美国人,我们的政策应当基于希望。来到美国的人应该怀有的是希望才对。大卫·米利班德(注:英国前工党政治家。我对米利班德的采访,参见:这次全球难民危机,是对我们人性的考验),就是国际救援委员会的负责人(注:致力于应对国际人道主义危机、帮助难民生存并重建家园与生活的组织),他是这么说的:“相比于在化武袭击中丧生的叙利亚人——来到美国的叙利亚难民数量还要更少。今年只有44名叙利亚人来到了美国。”这点让人很愤怒。

Last Word

寄语

Well, I want to thank you all for coming in and for listening. And I do think—I've never been kind of, you know, an agitator, but the bottom-line is, I do think that the university, community, and the questions were terrific, because they all lead to the question of what we do together. And I think we are in a very difficult time, and I am 80. And I don't want to end my life in a bad mood [LAUGHTER] about the United States. [APPLAUSE] So thank you very much. Thank you.

我想感谢大家前来倾听我的讲座。我从不认为自己是一名煽动者,但归根结底,我认为大学也好、社区也好,你们刚才的提问都很棒,因为这些问题都指向了我们一同在做的事。我认为我们正身处于一个艰难时刻。我今年80岁了,我不希望我走的时候,对美国的未来忧心忡忡。[笑] [掌声] 非常感谢大家,谢谢

特别鸣谢Leon对采访的翻译以及字幕制作

向杨的微博:向杨Alan

微信公众号:xy88chicago

本文作者系新浪国际旗下“地球日报”自媒体联盟成员,授权稿件,转载需获原作者许可。文章言论不代表新浪观点。